A general theory of social inequality

Economic- and social inequality continues to be a relevant topic in the public debate. But what are the fundamental causes of people’s different socioeconomic outcomes? In particular, in this text I will explore why people differ in educational attainment and income; because they are, by definition, a large part of what constitutes economic- and social inequality. Social scientists tend to overlook evidence from the field of behavioural genetics - a branch of science with the aim of untangling individual variation caused by heritable- and/or environmental factors (nature vs nurture). In 2015, the largest meta-analysis of twin-studies ever conducted was published by Polderman et al (link to study). The analysis included results for a vast number of traits, from almost 3000 studies and several million twin-pairs. The major finding was summarized by the authors as:

“Across all traits the reported heritability is 49%. For a majority (69%) of traits, the observed twin correlations are consistent with a simple and parsimonious model where twin resemblance is solely due to additive genetic variation. The data are inconsistent with substantial influences from shared environment or non-additive genetic variation.”

Let’s understand what the authors are saying. First, additive genetic variation refers to the phenomena that a trait depends on the accumulation of many small genetic variants (mutations); each of which affect the trait independent of each other. This means that the total genetic effect is just the sum of all the small effects. The aim of a twin study is to partition explained variance of a trait (the sum of which is always 100 %) into three parts, highlighted in the figure below.

We notice that environmental factors are subdivided into two kinds of environments:

1) Shared. Environment that both twins are exposed to. This is typically what you mean with upbringing and includes, for example, the parenting effect, the home environment and elementary school.

2) Unique. Environment that one twin is exposed to, but not the other. Generally, this category includes unknown factors such as random life events. One known example that has been shown to affect life outcomes, is traumatic brain injury (link to study).

So, Polderman et al found that heritable factors across all traits, could explain, in average, just short of half the variation in the outcomes. In contrast, they generally found shared environment to explain only a minor part. This research shows that heritable factors and unique environmental factors, in general, are the two big explanations as to why people differ from each other. But this is just an average of all traits and doesn’t tell us all that much about social inequality. I simply bring this research up because it gives a baseline position. If we know nothing about a particular trait, it is safest to assume that shared environment plays only a minor role, and that heritability and unique environment explain the majority of the observed differences in roughly equal amounts.

Educational attainment

With this in mind, let’s first explore educational attainment. According to the Polderman study, shared environment, unique environment, and heritability explain 27 %, 21 % and 52 % of the variance, respectively. This indicates that the family environment may considerably causally affect children’s level of education. Personally, I have regarded these results as perhaps one of the major areas where parents may affect their children’s social outcomes through nurture; 27 % of the variation is not negligible. There is a snag to this story though. To understand it, we have to understand the twin study design more deeply. Twin-studies compare the difference in correlations between genetically identical- and non-identical twins. This comparison assumes that non-identical twins are (like siblings) 50 % genetically related, whereas identical twins are 100 % related. For example, if all pairs of identical twins have reached exactly the same level of education and non-identical twins have too, we draw the conclusion that heritable factors must not matter at all. Conversely, if identical twins are 100 % similar but non-identical twins are 50 % similar, heritability must explain everything. The assumption that non-identical twins (and siblings) share 50 % of their genes seems reasonable enough. But it may in fact not be true for all traits because of something called assortative mating. Assortative mating occurs when couples tend to form pairs based on (genetic) similarity of a trait. If they do, then non-identical twins (and siblings) are expected to be more than 50 % genetically similar, for that trait. In twin-studies, this will reduce the difference in correlations between twin types and thus make shared environment look more important than it actually is. So, what evidence exists for assortative mating for educational attainment? In 2017, Robinson et al were able to answer this question by quantifying the genetic correlations between spousal pairs (link to study). The researchers analyzed the DNA of several thousand couples and predicted the educational attainment based on the genes of the partner. They found that the predicted educational attainments correlated within spousal pairs, with a correlation coefficient of 0.65. As a reference the correlation for height and BMI was 0.2 and 0.14 respectively. Interestingly, the phenotypic correlation for educational attainment was around 0.4, which means that spousal pairs are somehow able to sort on genetic propensity for educational attainment even better than their actual education level would reveal. According to a 2016 paper by Hugh-Jones et al; accounting for assortative mating and assuming a spousal genetic correlation of 0.5, diminishes the shared environmental contribution to zero and increases heritability of educational attainment to around 80 % (link to study).

Income

The other trait we will examine is income. In a 2019 study by Hyytinen et al, the authors performed a twin-study in a national database in Finland (link to study). They found that heritable factors explained 40-50% of the variation in life-time earnings. They also summarized several decades of research from similar studies from Sweden, Australia and the US (around 20 studies in total). In line with their finding, the average heritability estimates from the other countries were on average around 40-45 %. The Finnish study found “negligible” effect of shared environment, and the other country-specific findings ranged from 5 % in Sweden, 9 % in the US and 13 % in Australia.

Adoption studies

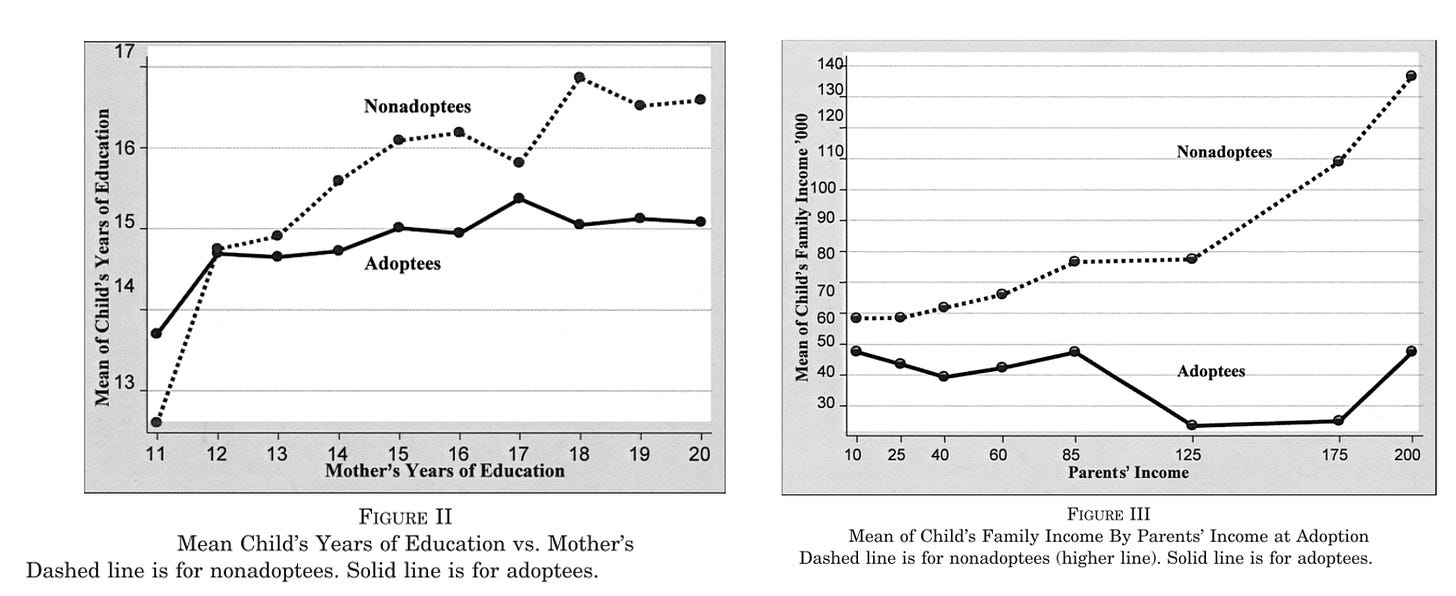

A separate test of the importance of home environment comes from adoption studies. In 2006, Sacerdote gathered data from adopted Koreans in the US (link to study). This cohort is rare since children were (close-to) randomly assigned into families of different socioeconomic status. Here, he was able to assess effects on both education and income, and the major results are seen in the figures below. In line with the twin-studies, a minority (around 11-14 %) of the variation in educational attainment and income was explained by shared environmental factors.

In summary, accumulated evidence from twin- and adoption studies point to a minor role of the shared environment in explaining differences in education and income between people. Instead, heritable factors are considerably more important, not least for educational attainment. Lastly, unique environmental factors may also play a substantial role for income.

A general theory of social inequality (in the UK)

I recently came across the work of an economist by the name of Gregory Clark. He has analyzed a large database of a historical lineage of 400 000 people in the UK, and their descendants, from 1750-2020. This database includes information on marriages, occupational status, income, education and wealth. In his working paper (link to study) he tests whether a simple genetic model can explain differences in social outcomes between individuals. The answer is yes, but only if a high degree of assortative mating exists. In his data, Clark also finds evidence of strong assortment, both in present times and throughout the centuries. The differences in education, occupation and income between people throughout this time period in the UK is therefore consistent with these differences being caused by (additive) genetic differences, and sustained through people’s partner preferences.

Conclusions

The current evidence consistently suggests that a majority of observed differences in income and education are best explained by heritability and unique environment, rather than by shared environment. This contradicts the main stream model that focuses on shared environmental factors such as parental styles, family environment/culture, social connections, schools and discrimination. If the prevailing model is wrong — and in fact genetics play a much larger role — attempts at improving social mobility by changing the shared environment is unlikely to have meaningful effects. Social inequality has been, and continues to be, one of the central political issues; with many suggestions on how to fix it. I remain unconvinced that various social-engineering programs will have meaningful effects in reducing socioeconomic gaps between people. Clarks notes in his working paper: “The Nordic model of the good society looks a lot more attractive than the Texan one”. I think his point is: if social mobility is low everywhere, don’t try to increase the rate at which people move on the distribution - instead narrow the distribution.